Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

The Curious Case of Benjamin Richardson: The recruitment consultant and the dodgy CV

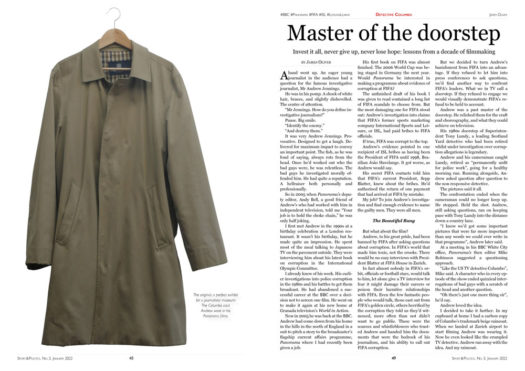

- James Corbett and Jens Weinreich

- 10. August 2020

- 23:55

- 2 Kommentare

Football Queensland president Benjamin Richardson has left behind a string of failed businesses, owing the Australian revenue at least $150,000 of unpaid taxes, while a bankrupt company under his control has drawn the condemnation of a liquidator for breaches of corporate law.

Richardson also misled voters when successfully standing for re-election as FQ President last month by circulating a curriculum vitae full of distortions and half-truths.

The scandal raises serious questions of FQ’s and FFA’s due diligence processes and is out-of-step with FIFA and the Court of Arbitration for Sport guidelines on integrity checks for senior level office-holders.

Richardson, along with FQ CEO Robert Cavallucci, is engaged in a spurious defamation case against Australian football activist, publisher and whistleblower Bonita Mersiades.

Richardson and Cavallucci are seeking $800,000 plus interest. They want to destroy Mersiades.

Putting this absurd, formidable demand against the backdrop of Richardson’s strange business practices, there may be some important answers.

We have written about the case here:

- How an out of touch federation is trying to destroy Australian sporting hero and whistleblower, Bonita Mersiades

- The curious case of Benjamin Richardson

We have also written about how the pair have used FQ’s money to try and divert attention from their actions by paying spin doctors huge fees:

Shortly after our publications on the dubious Ben Richardson case this website encountered at least two separate denial of service attempts and was not accessible. Investigators have told us some of these crude cybercrime attacks were linked to a single computer in Queensland, Australia.

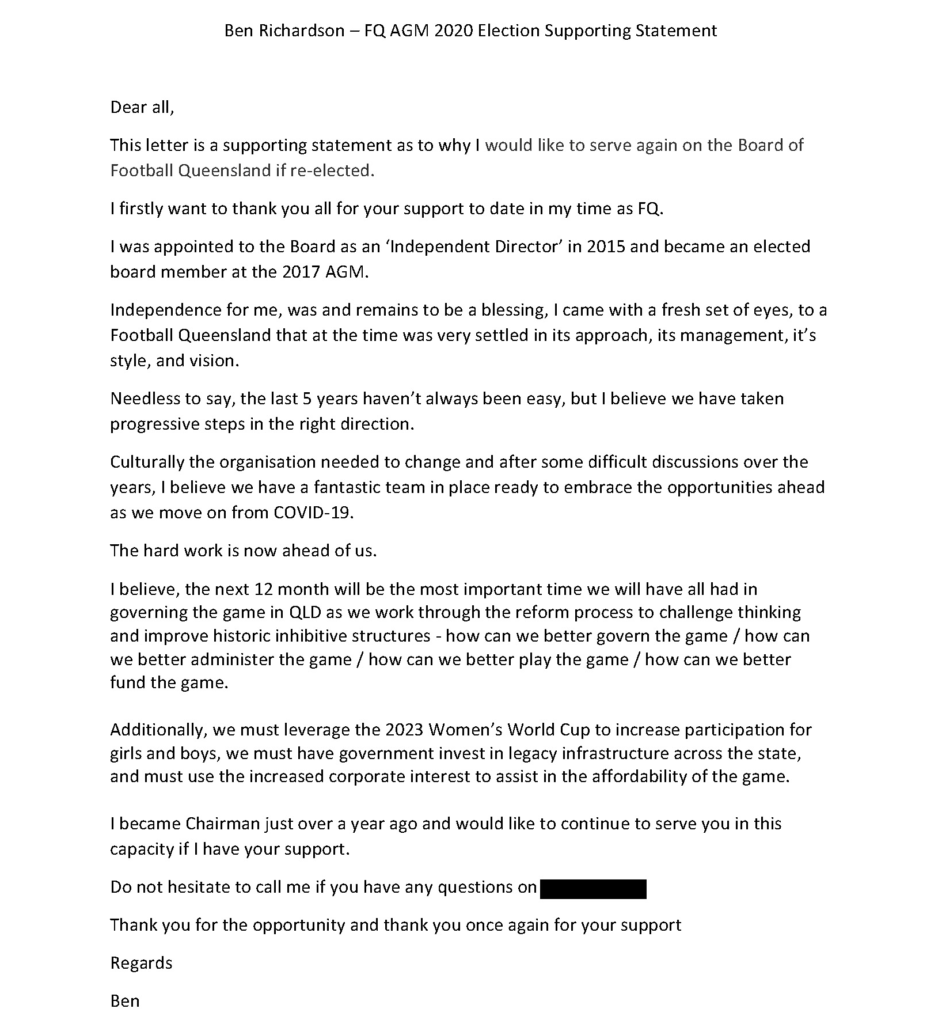

Ahead of Football Queensland’s elections last month, Richardson circulated a letter and a CV outlining his candidacy and credentials. Given that he has virtually zero web presence – which we find surprising given that his involved in recruitment – we welcomed this sudden accountability.

Unfortunately for Richardson – and football in Queensland – our checks via publicly available records on his career record raises more questions than answers.

This is what Benjamin Richardson is claiming in his CV. We have highlighted the (extremely) questionable parts.

Richardson, who was born in Nottingham, England in January 1979, came to Australia in the noughties having worked as an IT recruitment consultant with Alijon, which is now part of the Adecco recruitment group.

He claims to have been something of a teenage prodigy there, occupying the position of ‘principal’ – ‘a senior consulting role’ – before leaving aged 21.

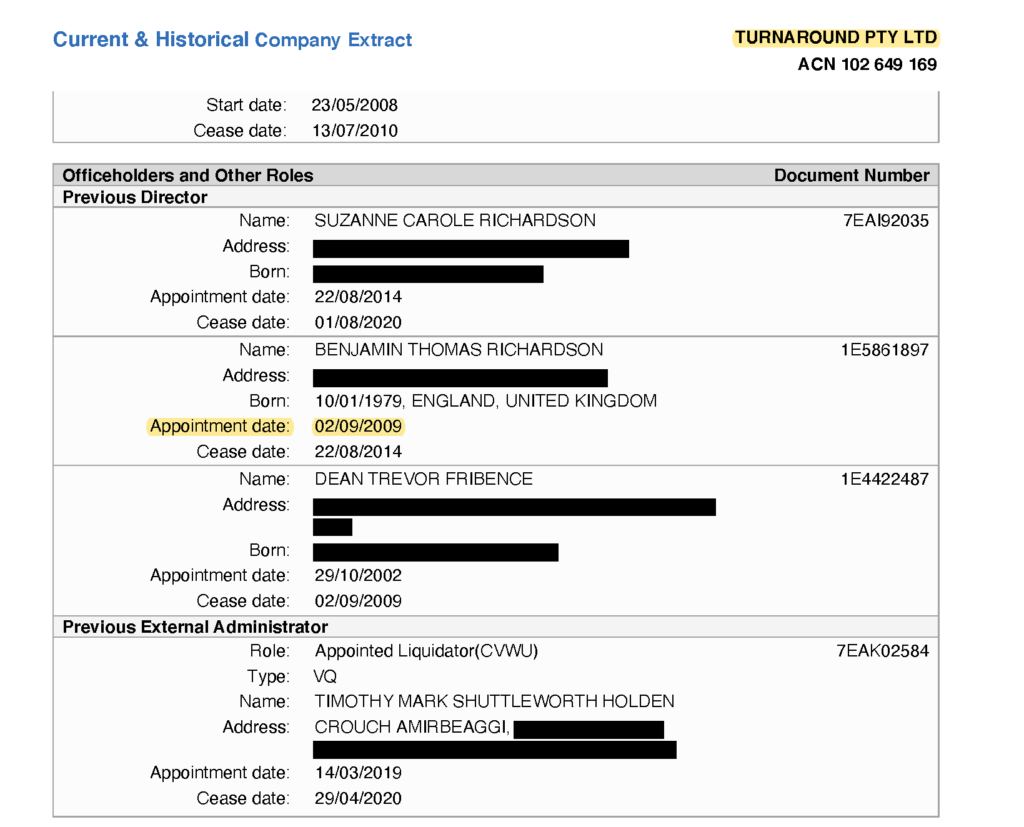

Yet it is when Richardson says he becomes involved in the Australian company, Turnaround Group in February 2001, as a ‚founding director‘ that serious questions start to arise about his credibility.

Submissions to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) show that this company was not incorporated until 20 months after Richardson said it was – when it was called DT Global – nor indeed was Richardson a ‘founding director’.

In fact ASIC records show that he did not become a director until September 2009, more than 8.5 years after he first claimed involvement. DT Global was renamed Turnaround PTY Ltd in May 2008.

We asked Richardson why he claimed to be a ‘founding director’ of a company 8.5 years before he assumed a director’s position. We also asked what he did in the intervening period.

He chose not to respond to our queries.

Unlike Britain’s Companies House, ASIC does not publish the balance sheets and summary accounts of private companies. So we are not able to ascertain whether there is any truth in Richardson’s assertion that the company turned ‘a $10million gross profit’.

It did have registered offices in one of Melbourne’s most famous addresses – Collins Street – and, later, Sydney and Brisbane, but the web imprint left by a company supposedly turning such a profit is minute. For the past two years Turnaround’s website has shown ‘inspirational quotes’ by figures such as JFK, Richard Branson and ‚Nelsom‘ Mandela.

We asked Richardson to show us records confirming the assertion that the company turned ‘a $10 million gross profit’.

He did not respond to our queries.

At a time when it was supposed to be showing these colossal profits, Richardson was living in a cottage in Armadale in Melbourne’s inner suburbs before moving to the neighbouring suburb of Malvern.

In 2014 – around the time that he is thought to have moved to Queensland – Richardson stepped down as a director of Turnaround and was replaced by his wife Suzanne Carole Richardson.

In August that year, according to ASIC records Turnaround gave up its address in Collins Street Melbourne and relocated to a residential address in the Brisbane suburb of Morningside. Its website nevertheless continued to list addresses in the CBDs of Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane until at least 2018, although it seems that the company had stopped occupying them by this stage. We have asked Richardson for clarification on this matter. Although his wife was the sole director, Ben Richardson continued to own Turnaround via his holding company, GL Melbourne.

Nevertheless, Turnaround faced significant problems, notably an unpaid six-figure tax bill.

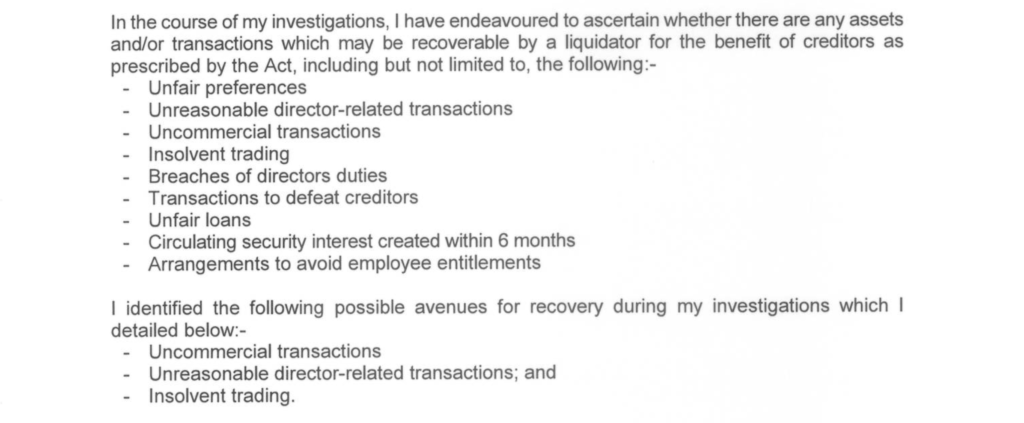

On 14 March 2019 Tim Holden of Crouch Amirbeaggi, a business and insolvency advisory, was appointed liquidator of Turnaround.

As principal director, Suzanne Richardson attributed the business’s failure to ‚the ill health of her external accountant leading to poor management of accounts and inadequate books and records.’ This led to ‘previously unknown taxation liabilities.’

The liquidator, however, portrayed a different picture.

The company had loaned Mrs Richardson $62,092, which she was unable to pay back. She claimed she was owed $10,000 and Ben Richardson was owed $30,000 ‘in relation to outstanding long service leave’. Holden, however, said there was ‘no formal proof or evidence in relation to these debts.’

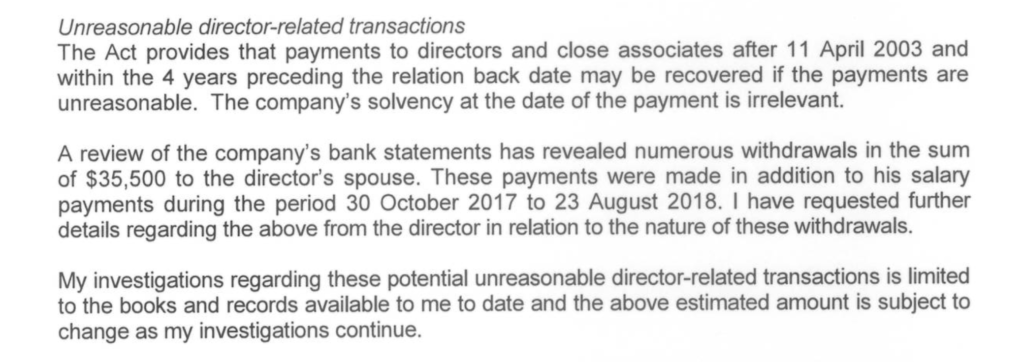

Indeed Holden was damning about Ben Richardson’s conduct. He found ‘numerous withdrawals’ made by Richardson between 30 October 2017 and 23 August 2018 ‘in addition to his salary.’ These amounted to $35,500.

In addition, the liquidator found that Richardson’s wife had overseen the company trading whilst insolvent since at least December 2018, leaving a potential insolvent trading claim of $85,000 against her. In Australia a director has to personally indemnify any costs related to trading while insolvent.

Nevertheless, he added that her lack of ‘any material personal assets’ would leave her incapable of settling any claim brought against her.

Insolvent trading is punishable in Australia by a fine of up to $220,000 or imprisonment of 5 years, or both.

On top of this, the liquidator found $109,148 owing to the Australian Taxation Office.

We find it strange that the main shareholder of a company that was making a ‘$10million gross profit’ even as long as a decade ago is unable to repay these relatively modest amounts. Or indeed why he would be making ‘numerous withdrawals’ from the company accounts on top of his salary.

Curiously, when Richardson sent an invoice to FQ in November last year, it contained Turnaround’s logo and asked for remittances to be sent to a Turnaround email address. Mysterious.

In total Tim Holden was able to recover $61,806 for creditors. $50,000 of this was paid for his insolvency services, with the surplus being divided amongst unsecured creditors, including the Australian Taxation Office – who would have gotten around 10c in the dollar that they were owed.

According to ASIC, Turnaround Pty Ltd was formally deregistered as a company on 1 August 2020, a week after Richardson was re-elected as Football Queensland president – an election in which he’d bragged about the success of this soon to be defunct company.

Missing companies

Richardson lists himself as chairman of Personnel West Disability Services Company. We have asked Richardson for more details about this company because there is no record of Personnel West Disability Services Company with ASIC. We did, however, find details of a Personnel West and a merger is confirmed in the Endeavour Foundation’s 2013/14 annual report.

We have also looked into other claims about his role as a ‘Ned/Investor/Consultant’.

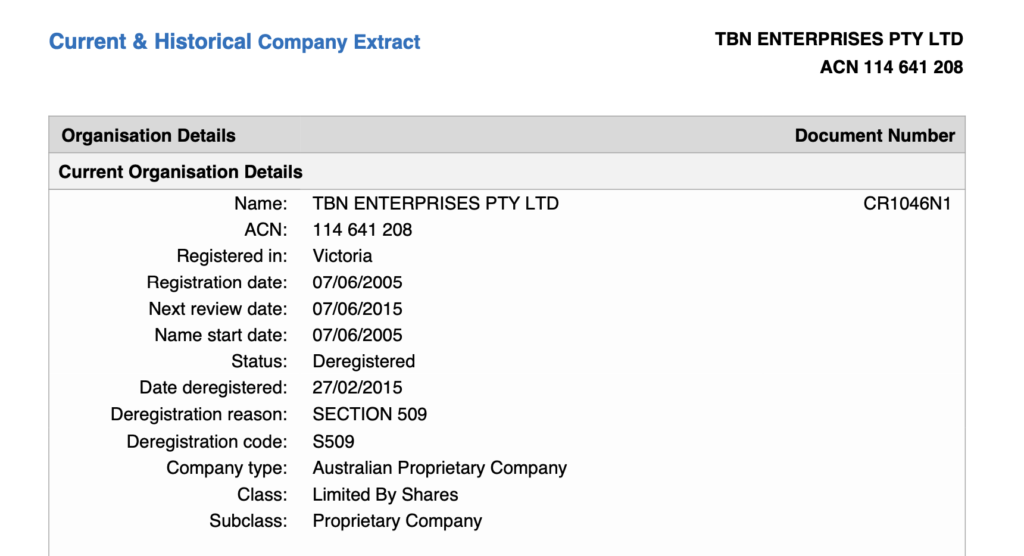

Richardson was a shareholder of TBN Enterprises via GL Melbourne, another company that went into liquidation in July 2012. This failed business left $114,072.10 of unsecured debts to three creditors, who received just 4.66cents in the dollar.

As with the collapse of Turnaround the main creditor was the Australian Taxation Office, which received just $3381.35 of $49,692.61 owing to it. Again Tim Holden – then of Foreman’s – was appointed administrator, on a rate of $605 per hour – to clear up Richardson’s mess. TBN Enterprises was deregistered on 27 February 2015:

Richardson – via his holding company – was a 50% shareholder in Mining for Talent (2009-17), Crosskeys Recruitment (2008-2017) and CK Search (2013-18), all of which were deregistered under S601AB of the Corporations Act.

There are a number of reasons why this legislation may be used, usually when assets in an insolvency are not significant enough to cover the costs of a liquidator. We asked Richardson for clarification on why these companies were wound up.

He did not reply to our questions.

Richardson is currently a 33% shareholder in BigRoo Holdings, which owns Aspirante, a recruitment company headquartered in Brisbane, Sydney and Melbourne. He is also a 30% shareholder in BigMac Holdings. Big Mac owns 50% of Emergence Talent, a specialist IT recruitment company.

Voluntary work

Richardson makes a great play on his role in volunteerism. He is chairman of the Liver Foundation, a small charity that promotes liver health and research. Its governance details and records are here.

Unfortunately they don’t match the details on his CV.

The CV says he became a NED/Chairman of the Liver Foundation in April 2012. But we’ve looked through its annual reports to check this.

- 2013: no mention of Richardson

- 2014: no mention of Richardson

- 2015: no mention of Richardson

- 2016: no mention of Richardson

- 2017: no mention of Richardson

- 2018: first mention of Richardson

Richardson gave a rare interview to ABC on 20 October 2018, in which he said he first became involved with the Liver Foundation ‘3-4 years ago’. If you go to 4mins 45secs you can hear him doing so.

But his wife Suzanne gave an interview with the Brisbane Courier-Mail in June 2014 in which she says that Ben joined the board of the Liver Foundation in 2010 – two years before even he claims to have done.

Confused?

When Richardson starts talking about his role in football things start to get confusing again. Under his time at FQ there is no mention, for example, about his self-styled time as ‘interim CEO’ – which seems an extraordinary omission if it’s not as a colleague described to us (‘complete bullshit’).

He also says he is on the ‘Rem & Noms Committee’ of the Football Federation Australia (FFA), which is interesting – because FFA say no such committee exists, as Matthew Hall reports. This is what an FFA official replied to him:

‚I’ve looked into this for you, and FFA doesn’t have a ‘Rem & Nom’ committee. There is a ‘Nominations Committee’, which includes members nominated by Congress members, however Ben Richardson is not a member of that committee. Hope this helps.‘

[11 August, 7.53 CEST: We have updated the last two paragraphs, and we have sought further clarification on this point, although the FFA response was clear and we have quoted it correctly. Richardson also ignored our questions on that matter – see below.]

Richardson lists governance and leadership as one of his strengths. A hallmark of both is accountability.

Once more he has failed to answer our questions, which we list here:

1) You describe yourself as a ‘founding director’ of Turnaround from February 2001. ASIC records shows that this company was not in fact incorporated for a further 20 months, when it was founded as DT Global. They also show that you did not become a director until September 2009, more than 8.5 years after you first claimed involvement and 15 months after it was renamed Turnaround PTY Ltd.

a) Why did you claim to be a ‘founding director’ of a company 8.5 years before you assumed a director’s position?

b) What did you actually do in the intervening period 2001-09?

c) When did you leave the UK for Australia and what were the initial purposes of your relocation?

2) Your CV cites that Turnaround turned ‘a $10 million gross profit’. Please can you evidence this with abbreviated accounts or a corporate tax return to that effect. We will redact any confidential information as a matter of journalistic duty.

3) In August 2014, ASIC records show that Turnaround gave up its address in Collins Street Melbourne and relocated to a residential address in the Brisbane suburb of Hawthorne. Its website nevertheless continued to list addresses in the CBDs of Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane until at least 2018. Can you clarify why you relocated the company’s principal place of business to a residential address while publicly maintaining these blue chip office spaces?

4) After Turnaround went into liquidation, the liquidator Tim Holden found ‘numerous withdrawals’ made by you between 30 October 2017 and 23 August 2018 from Turnaround accounts ‘in addition to his salary.’ These amounted to $35,500. Can you clarify what these withdrawals related to and confirm that if it was for personal income that taxation was paid on the amounts?

5) Your wife Suzanne was from 2014 the sole director of Turnaround, despite you being the only shareholder via GL Melbourne. Shortly after his appointment in March 2019 the liquidator found that she had overseen the company trading whilst insolvent since at least December 2018 (10 weeks), leaving a potential insolvent trading claim of $85,000 against her. In Australia a director has to personally indemnify any costs related to trading while insolvent.

a) How did the company rock up such significant losses in so short a period of time?

b) As principal shareholder what oversight did you have on this period of insolvent trading?

6) Eight months after liquidators were called in to Turnaround, you issued an invoice to Football Queensland for $44,000 on behalf of Ben Richardson Consulting. This invoice contained Turnaround’s logo and asked for remittances to be sent to a Turnaround email address. Please account for this.

7) Via your holding company – GL Melbourne – you were a 50% shareholder in Mining for Talent (2009-17) and CK Search (2013-18), both of which were deregistered under S601AB of the Corporations Act. There are a number of reasons why this legislation may be used, usually when assets in an insolvency are not significant enough to cover the costs of a liquidator. Please clarify the circumstances of the insolvencies of:

a) Mining for Talent

b) CK Search

c) What liabilities were owed to the Australian Taxation Office in these cases.

8) Your CV omits your self-styled time as ‘interim CEO’ of Football Queensland. Why?

9) You say that you are on the FFA’s ‘Rem & Noms Committee’, which is interesting – because after a specific query on this by a colleague, FFA say no such committee exists. There is, however, a nominations committee – but Mr Richardson is not on it according to FFA. Please clarify which, if any, FFA standing committees you are actually on.

It is also apparent that FFA’s and FQ’s Constitutions and Codes of Conduct do not make suitable provision for appropriate independent checks of members of its most important bodies.

The Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) has a number of rulings on issues of integrity of candidates, which arose from the FIFA reforms of 2016. FIFA’s own internal guidelines on this issue note CAS’s view ‚that an integrity check is rather an abstract test as to whether a person, based on the information available, is perceived to be a person of integrity for the function at stake …‘.

CAS went on to state that a candidate for high office ‚must under any circumstance appear as completely honest and beyond any suspicion. In the absence of such clean and transparent appearance by top football officials, there would be serious doubts in the mind of the football stakeholders and of the public at large as to the rectitude and integrity of football organizations as a whole.‘ (CAS 2011/A/2426, §129).

On this occasion, CAS has got it right.

Over to FFA.

It’s time to adhere to FIFA reforms and take steps to clean up the sport in your country.

Note: We must emphasise that all documents quoted here are in the public domain.

Sie wollen Recherche-Journalismus und olympische Bildung finanzieren?

Do you want to support investigative journalism and Olympic education?

SPORT & POLITICS Shop.

Subscribe to my Olympic newsletter: via Steady. The regular newsletter is free. Bur you are also free to choose from three different payment plans and book all product at once!

-

„Corruption Games“ E-Book19,90 € – 99,00 €

„Corruption Games“ E-Book19,90 € – 99,00 €inkl. MwSt.

-

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 39,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 39,90 €inkl. 7 % MwSt.

-

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 19,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 19,90 €inkl. 7 % MwSt.

-

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 29,90 €

SPORT & POLITICS Heft 29,90 €inkl. 7 % MwSt.

-

Business-Paket600,00 €

Business-Paket600,00 €inkl. 7 % MwSt.

Pingback: The case of Ben Richardson and the accomplices in the Football Federation Australia, in media and even Sport Integrity Australia - SPORT & POLITICS

Pingback: Football Queensland: The nightmare before Christmas - SPORT & POLITICS