Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

A decade that opened windows of democracy in sport

- Jens Sejer Andersen

- 1. Januar 2020

- 20:20

- 2 Kommentare

Zum neuen Jahr, zum neuen Jahrzehnt: Ein Kommentar meines Freundes Jens Sejer Andersen, Gründer und Direktor Internationales der Organisation und Konferenz Play the Game.

It was not primarily the athletes that drove the radical change of the sports agenda in the decade we leave. But there are signs that athletes will be at the heart of the agenda of the 2020’ies, writes Play the Game’s international director in a wind-up of ten turbulent years in world sport.

Try to think ten years back (if you are not too young or too old to remember):

If someone had told you, at the doorstep of 2010, that the following decade would

- show at least one million of Brazilians taking to the streets, combining their outrage over government policies with protests against the FIFA World Cup, and sending shock waves through the Olympic movement

- have 15 cities around the world withdraw their bid for hosting Olympic Games after referendums, or out of fear for how taxpayers and voters would react

- reveal a long-term, systemic doping programme orchestrated by one of the world’s most powerful nations in sport and politics, the Russian Federation, forcing prominent whistleblowers to seek asylum elsewhere and causing deep divisions in international anti-doping

- see the U.S federal police raid a FIFA congress in Switzerland, exposing unknown corruption scandals worth hundreds of millions of US-dollars, eventually imposing huge fines and long jail sentences to numerous football officials

- grant one of the two largest sporting events in the world to a tiny desert state, unleashing a global debate about slavery-like work conditions in Qatar and other Arab countries, and human rights violations in sport at a general level

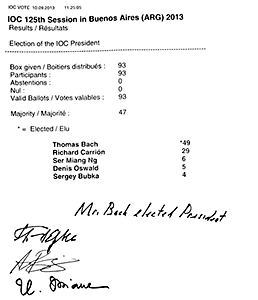

- see a Vice-President of the International Olympic Committee arrested during the Olympic Games, with cameras rolling, and a handful of other members of the inner Olympic power circles retire due to criminal investigations across the world

- hear over 150 women testify on the massive sexual abuse they were exposed to over two decades by a physician of the USA Gymnastics team and Michigan State University, adding their stories to dozens of similar cases affecting the lives of boys and girls, in the UK, France, Norway, Nigeria, the Netherlands…

Would you have found such predictions for international sport credible?

Or would you have regarded them as wishful thinking by “negative people who tried to build a career by criticising the good work of sport” – as an official from the very top of international sport in 2009 kindly characterised Play the Game and the speakers we brought along?

Honestly, I don’t think even the most critical, most negative, most conspiracy-loving follower of Play the Game in 2009 could imagine the real scope of the crime and corruption challenges woven into modern sport.

Back then, the solid evidence brought forward by investigative journalists, whistleblowers, researchers, and prosecutors, was already bad enough to conclude that sport had a serious and inherent integrity problem.

Sports officials would most often dismiss their well-founded revelations as exaggeration and fantasies, but the 2010s proved that reality also in sport often surpasses imagination.

It can be hard to draw hope and inspiration from the above-mentioned sports scandals and many others we have experienced in the last decade. After all, they have all come at a high price for those who suffered the consequences. Corruption is not a victimless crime: Ask Mario Goijman, ask Yuliya and Vitaly Stepanov, ask Phaedra Almajid, ask Bonita Mersiades, ask Sandro Donati, ask any whistleblower around in sport.

But thanks to these courageous people, thanks to investigative journalists, thanks to honourable public servants, the 2010s brought a remarkable difference: Silence was finally broken. A few examples:

Until 2010, the integrity problems were most often hushed or played down, no matter how hard the evidence. Match-fixing was ignored. Sexual abuse cases were oppressed. The IOC stressed it was not a human rights organisation. Corruption flourished in international federations. FIFA bribes worth 142 million Swiss francs were documented in Swiss courts in 2008, but did not catch many headlines, and sports leaders kept silent.

Matter of public interest

Today, the integrity challenges of sport are highlighted at every major sports conference. Governments have started making policies for better sports ethics. A centre for sport and human rights have been established. Anti-Olympic campaigners have formed a global alliance. Athletes unions, too. An international convention against manipulation of sports competitions has been ratified. Every sports federation in the world, even the most backwards, claims its heartfelt commitment to good governance.

All in all, sports politics have become a matter of public interest. Ten years ago, you would spend ten minutes surfing the internet to get a full overview of the day’s sports political stories. Today, the production is overwhelming, and Google is probably the only entity able to get a full overview.

Many questions can rightly be raised about the quality of the media reporting, the efficiency of government policies, the futility of public interest, and the credibility of the Olympic movement’s interest in reforming itself.

What is undeniable, however, is that windows of opportunity have been opened over the past ten years for groups who, like Play the Game, pursues more democracy, transparency and freedom of expression in sport.

And it should foster optimism to see how these groups are growing in numbers and strength. They grow among grassroot activists, they grow in parliaments. They grow in the media, they grow at universities. They grow in emerging and trendsetting sports activities, and they even grow inside the sports bureaucracy in the Olympic capital of Lausanne, Switzerland.

What is particularly important, is the growing trend among the athletes themselves to organise and let their voices be heard.

Growing appetite for influence

It was not primarily the athletes that drove the radical change of the sports agenda in the past decade. But there are many recent signs that professional athletes have a growing appetite for influencing their own arena and society at large. Sporting icons like NFL player Colin Kaepernick, and football players like Megan Rapinoe and Mesut Özil have spoken up against racism, discrimination and persecution of minorities.

At the bottom of the competitive pyramid, athletes have voted with their feet for more than a generation, seeking health, fun, and good company far well outside the classic sports system.

Athletes of all kinds will likely be at the heart of the sports political agenda of the 2020s, and their working range may stretch well beyond sport itself.

One of the most important challenges of the next decade will be to develop the forms in which athletes can best express their individual and collective visions, negotiate their disagreements, and influence the decisions that decide the future course of sport.

The old forms of sports politics, the global pyramid of associations and federations, must undergo dramatic reforms just to keep their relevance, and they must, in any case, accept to live side by side with new ways of making politics. Just as the era of silence is over, so have the days of monopoly come to an end in the world of sport, play and physical activity.

Happy New Decade, Happy New Year!

Cross-posting von Play the Game. Offenlegung: Ich habe an allen zehn Play-the-Game-Konferenzen seit 2000 teilgenommen, seit 2007 bin ich ehrenamtlich für alle Konferenzen im Programmkomitee engagiert. 2011 erhielt ich gemeinsam mit meinem Freund Andrew Jennings den Play the Game Award für unsere langjährigen Recherchen zur FIFA-Kriminalität.

Ich wünsche allen treuen Lesern ein gesundes und erfolgreiches neues Jahr!

Das neue Jahrzehnt fängt erst nächstes Jahr am 1.1.2021 an. :)

Schlaumeier!

Ich lass das dennoch mal so stehen, solange es keine Post irgendeines Abmahn-Anwalts gibt.

‚Jahrzehnt‘ = ‚zwanziger Jahre‘ … dann kommt es ungefähr hin.