Das Olympische Bildungsmagazin

„Bribes as salaries for sports leaders“

- Jens Weinreich

- 19. Oktober 2010

- 15:23

- 5 Kommentare

Mein Freund und Kollege Jens Sejer Andersen hat vergangene Woche an der Universität Antwerpen einen Vortrag zu einem ewig aktuellen (und derzeit wieder brandaktuellen) Thema gehalten, den ich gern veröffentliche. Es tauchen viele der üblichen Verdächtigen und alten Bekannten auf, ob nun der Handball-Pharao, Ruben Acosta oder Jean-Marie Weber. (Aus Zeitgründen muss ich leider weitgehend auf Verlinkungen verzichten, zu allen gibt es im Blog etliche Geschichten.)

Voilà:

The Magicians of Sport: How the Greatest Corruption Scandal in World Sport Vanished Before We Knew It Existed

By Jens Sejer Andersen

International Director and founder, Play the Game

Usually, I am a great admirer of magicians. People who can make elephants appear out of nowhere or escape from underwater cages hand-cuffed and wrapped in chains, really deserve respect.

There are, however, some magicians that we should beware of, and quite a few of them do their tricks in sport. I am not referring to artists like Lionel Messi or Justine Henin who can make unimaginable things with a ball. No, the magicians I would like to talk about are exercising their witchcraft more discreetly.

They do not seek our admiration over their skills. On the contrary: They shun the public eye so much that they have become experts in one aspect of magic: They know how to make us look in one direction while they do their work in the other direction, and more than that, when we look back we do not even notice something mysterious has happened.

Thanks to these magic abilities, a number of corruption scandals in the highest ranks of sports leadership continue to vanish, even before we realise that they actually exist.

Where were for instance your eyes looking in late June this year? I suppose that they, like mine, were directed at a flat screen TV to follow the last matches in the group stage of the FIFA world cup in South Africa.

Abracadabra! While we were staring on one of the greatest shows on earth, the biggest corruption scandal ever documented in sport disappeared out in the blue.

Did you notice?

If not, don’t feel ashamed. It was not meant for you to see.

While events in South Africa spellbound the world, a dry and formal sheet of paper was produced more than 8,000 kilometres away, by the public prosecutor in Zug, the Swiss canton in which FIFA resides.

On the 24 June, the prosecutor ended eight years of legal proceedings with a statement that put an end to the so-called ISL-affair.

Simultaneously, FIFA noted in a very brief media release “FIFA is pleased that the prosecutor of Zug has finalised his investigations�?.

FIFA had reasons to be satisfied indeed. For although the Swiss prosecutor that day confirmed that FIFA officials had received millions of Swiss francs from the ISL company and kept them in their pockets, and that FIFA should pay a compensation of 5,5 million Swiss francss – around 4 million euros – things could have turned out much worse for football’s governing body.

The collapse of a marketing giant

For the ISL was no street vendor of services to FIFA. ISL stands for International Sport and Leisure and was from the early 1980’ies and until its collapse in 2001 by far the biggest sport marketing company in the world. It was founded by the Horst Dassler, whose family owned Adidas.

ISL bought TV and marketing rights from the international sports federations and the International Olympic Committee and re-sold them to media companies and private sponsors. Thanks to its close personal relations to FIFA and other big federations it became a driving force in the explosive commercialisation of elite sport.

However, even a booming company in a booming sector can make mistakes, and in 2001 the ISL collapsed because it had seriously overestimated the value of its products.

When the Swiss administrators took over the bankrupt ISL and started looking at the internal papers, they soon discovered some strange payments. In the first place, the liquidator of the company, Thomas Baur, found that at least 3,5 million Swiss francs (at the time 2,2 million euros) had been paid out in personal commissions and they started writing leading sports officials in order to get the money back.

And in 2004, Mr Bauer did get most of that money back. Not in many small portions, but on one big check of 2,5 million Swiss francs. It would of course be interesting where this sum came from and on behalf of which sports leaders it was paid back, but after hard work from a splendid Swiss lawyer, Peter Nobel – the Federal Court, the highest court in Switzerland, ruled that no names should be named.

Peter Nobel is not only an excellent player in the court room – a magician in his field you may say – he was also the man who issued the big check. And, coincidentally perhaps, he has for many years been the personal lawyer of Joseph S. Blatter, President of FIFA.

But this was only the beginning. Other parts of the Swiss justice had an interest in the ISL, and one investigative judge, Thomas Hildbrand, was particularly active, launching firstly one investigation into how six ISL-directors managed their affairs, and secondly another one into the relation between FIFA and the ISL.

138 million Swiss francs in kickbacks

In 2008, the court in the Swiss city of Zug concluded the first of these two cases, the proceedings against six former ISL directors for embezzling large portions of money belonging to FIFA. The legal case itself ended up with acquittals and mild sentences since the defendants could convince the judges that FIFA in reality had accepted the way ISL handled FIFA’s money.

But in the indictment a stunning revelation was brought forward and confirmed by the defendants in the court room:

Over 12 years, from 1989 to its bankruptcy in 2001, ISL handed out no less than 138 million Swiss francs – then 87 million euros – in personal commissions to sports leaders in order to get lucrative TV and marketing contracts.

The payments were channelled to the private pockets or bank accounts of high ranking sports leaders through an advanced system of secret funds in Liechtenstein and the British Virgin Islands. Some of the kickbacks were handed over personally by the top executive of the ISL, Jean-Marie Weber, who travelled around the world with a suitcase filled with cash.

Bribes as salaries for sports leaders

According to the defendant ISL directors, these payments were a normal and integral part of the daily sports business and a precondition if ISL wanted to sign contracts with their customers.

“I was told the company would not have existed if it had not made such payments,�?

said former chief executive of the ISL Christoph Malms, and was backed the former director of finances, Hans-Jürg Schmid.

“It was like paying salaries. Otherwise they would have stopped working immediately�?,

he said about the sports officials.

How come that the six directors admitted these secret personal commissions so freely? The answer is simple. In Switzerland this kind of kickbacks or bribes were not criminal until new anti-corruption legislation was passed in 2006.

And although the directors were quite open-mouthed, they did not risk their future career by dropping names in the court.

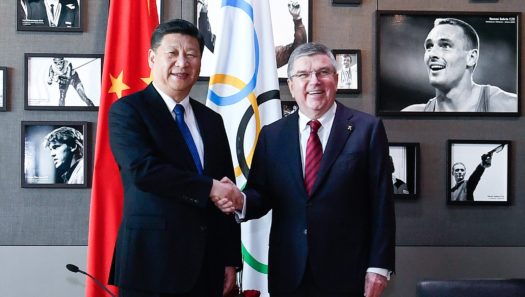

We only know that when ISL flourished, some of its most important customers besides FIFA were the ATP in tennis, IAAF in athletics, FINA in swimming, FIBA in basketball and for some years also the IOC.

You would perhaps expect that these organisations did react to the revelations in Zug by tracing corrupt sports leaders in their own ranks or at least distancing themselves publically from such malicious practices.

But no: From the international sports community there has only been one reaction to what is beyond comparison the biggest known corruption scandal in sport: Unanimous and complete silence.

After the verdicts in Zug 2008, there was still a hope: Perhaps the third and last criminal investigation could help us answer the simple question: Who took the bribes?

How much did they get each? – after all, 87 million euros is a lot of money, and not that many persons were in charge of TV and marketing contracts. Do these persons still hold important positions in sport?

Unfortunately, the end of the ISL affair this summer did not answer any of these questions.

The settlement does confirm what FIFA has long denied: That FIFA officials have taken millions of Swiss francs from the ISL in return for contracts. And it does oblige FIFA to pay back some of the money stolen from sport.

But even if we assume that all cheques have been paid by FIFA: 2,5 million Swiss francs to the liquidators, 5,5 million Swiss francs in the recent decision plus the costs of the legal procedure – we are still far from the impressing 138 million Swiss francs that went with the corruption. The financial balance is clearly in favour of those who cheated.

Before I go deeper into analysing the mechanisms that allow such a huge scandal to run almost unnoticed by the world public, one more important question arises from the ISL case:

Is the magic over?

Did corruption in sports organisations die with the ISL in 2001, and is the buying and selling of TV and marketing rights now a clean business?

No answers given at Olympic congress

I raised this question during a session about “Good governance and ethichs�? at the Olympic Congress in Copenhagen last year where over 1,200 high ranking sports officials gathered to discuss the challenges to sport. The answer from the moderator, Youssoupha Ndiaye from the IOC Ethics Commission, was easy to understand:

“The panel does not answer questions�?.

To be fair, the audience was quite amused by that response. Well, perhaps not all – probably not the man sitting a few rows from me, Jean-Marie Weber, the man who once travelled the world with a suitcase full of money.

I do not know which tasks the elegant Weber had at the Olympic Congress, but it cost the IOC President Rogge some sweat explaining Weber’s presence. It was apparently not the IOC itself that had invited him, but to get an accreditation through the strict security measures of that meeting you had to have very good connections in the so-called Olympic family of sport.

Only several weeks after the congress Rogge declared that Weber would not get Olympic accreditation in the future.

Although Jean-Marie Weber was in his time without comparison the most influential sorcerer in sport, he was not and is not the only one, and there are several cases that prove that corruption in sport did not vanish with the bankruptcy of the ISL.

The royalties of volleyball

Take for instance the great leader of world volleyball from 1984-2008, Ruben Acosta from Mexico – or Dr. Acosta as he prefers to be called though no papers supports this doctorial title.

As a President of the Federation Internationale du Volleyball (FIVB), Ruben Acosta – very actively assisted by his flamboyant wife Malú – introduced a kind of management style that is comparable to absolute monarchy.

Ruben Acosta made the FIVB a resounding commercial success: He changed the counting system of volleyball, he decreed tiny shorts for female players, and last but not least: He embraced and developed beach volley with its flavour of sun, sex and soft drinks. All these initiatives were aimed at making the ailing sport more appetizing on the TV screens.

And here we go again: While you and I were staring at the suntanned men and women playing in the sand with very little clothes on, the magician went to work.

Without asking anyone he introduced a rule by which every person who signed a TV or marketing contract on behalf of FIVB, was entitled to a personal commission of 10 percent of the contract sum.

He also introduced another rule: That the president signs all contracts.

According to their critics, this procedure may have secured at least 25 million US-dollars for the Acosta family.

Sooner or later this practice had to be ratified by the General Assembly. When some volleyball leaders began to question them, a code of conduct was soon introduced, according to which anyone who criticises volleyball or its institutions, could be excluded by the president.

On that account, several respected international volleyball leaders have had to retire involuntarily in the last decade. They are not even allowed to enter the local volleyball club, so in fact they are deprived of a basic civic right, the right to take part in association life.

Removed critical auditor’s note

But even magicians sometimes fail. When the FIVB accounts for 2001 showed that Ruben Acosta that year alone had received 8.4 million Swiss francs, over 5 million euros in personal commissions, Acosta decided to hide the number by grouping it with other amounts. Perhaps he thought that the General Assembly would not be able to handle such a big figure.

The auditors, however, took the rare step to make a critical note in the accounts because the personal commission was not transparent. This made Acosta even more worried: How would the General Assembly be able to hand such a complex message?

So in order not to confuse the delegates, Acosta simply decided to delete the critical note of the auditors before the FIVB accounts was published. This action is illegal in most countries, even in Switzerland.

So in 2006 the local court in Lausanne decided that Acosta and his nearest aides at the FIVB offices had really done something wrong. But as the judge felt that no harm had been done and there had been no criminal intent, Acosta was acquitted. His only obligation was to pay legal costs in the amount of 4.300 Swiss francs. Again, a good financial balance for the cheater.

Acosta’s magic tricks did not go unnoticed at the IOC. The IOC’s Ethics Commission produced a devastating report about Acosta’s mismanagement already in 2004. But as Acosta reacted by leaving his IOC seat in anger and protest, the IOC decided to keep the report secret, and Acosta got four more years to harvest the money that belonged to volleyball.

The handball Pharao

Acosta’s successor from 2008, long-standing Vice-President Jizhong Wei from China, has fortunately decided to replace his loyalty to Acosta with a loyalty to his sport. Wei has stopped all payments to Acosta, upsetting many of Acosta’s friends, and he has taken many other positive steps. But he has still not succeeded in rehabilitating those volleyball leaders that were excluded from all volleyball because of a sense of ethics.

This sensibility is not predominant in another sport where the top grabs for more than the ball.

The Egyptian business man Hassan Moustafa has had a firm control of the International Handball Federation for the past ten years and has his own way of understanding good governance.

It is well documented that he has tried to influence the outcome of Olympic qualifiers. That he has travelled for over 300,000 euros without presenting receipts. And that he has demanded insight into the doping testing plans for national teams.

At the General Assembly of the IFH in Cairo last year, it was also evident that the European opponents were not allowed to speak. A rival for the presidency, the Luxembourger Jean Kaiser, simply had his microphone cut off.

These facts did not impress the assembly which re-elected Hassan Moustafa by an overwhelming majority, 115 against 25. A similar majority ousted the long-standing secretary general Peter Mühlematter, who had dared to tell the public what Moustafa was doing with handball’s money.

Earlier this year a new story has been confirmed. From 2007 to 2009, Hassan Moustafa was employed as an advisor for the German marketing company Sportfive. Moustafa’s salary was 602,000 Euro.

Curiously, in that same period, Sportfive acquired the TV rights for the International Handball Federation.

And even more curiously: When Sportfive’s director, Robert Müller von Vultejus, left his position and went to rivaling company UFA, a quite new player in sports marketing, this company won the next bid for the IHF TV rights. Thought-provoking, isn’t it?

The Bermuda Triangle: Sport, sponsors, media

Would it have hindered the re-election of Moustafa if his constituency had heard about these magic events?

I guess not. Moustafa is simply a typical representative of the power structures that international sport has developed since the early 1980’ies, thanks to visionary businessmen like the late Horst Dassler.

30 years ago a triangle was created which you may call the Bermuda Triangle of sport – a triangle where transparency, accountability and true democratic standards always disappears mysteriously.

Roughly explained the triangle has three legs that support each others: sports organizations, multinational companies and TV companies.

Adidas and other consumer goods producers give sponsorships to sports organizations to ensure that they are run by people with the right mindset – some of the first to benefit from this was the late IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch and the former FIFA President Joao Havelange.

In return, these outstanding sports leaders ensured that their sponsors got exposure and access to emerging markets everywhere in the world. By signing marketing contracts with national federations the sponsors could get an even stronger foothold on local markets.

The globalization of the TV media was of course a driving force in this development. TV companies saw the potential of elite sport to build up audiences and were willing to invest huge sums in acquiring broadcasting rights. These rights were paid either with tax-payers’ money – or in case of private TV companies, with money from advertising by consumer goods producers.

TV and corporate companies have one thing in common. They are on a highly competitive market. They need sport in this competition, and they are ready to raise the stakes to get sport on their side.

This has been to the great advantage of sports organizations which in their turn are on a market with very low competition. Within each sport, they are de facto monopolies. Internationally and nationally there is only one federation in every sport.

As a result, sport has been able to gather ever-increasing revenues from the sponsors as well as from media companies.

A breeding ground for corruption

Much of this money has been used by the sports presidents to globalise sport and strengthen their own position. The main procedure has been to establish new federations in poor countries with no structure for athletics, handball, volleyball or any other sport and to provide these new federations with generous grants and other kinds of privileges. They have been so eager to recruit new members that FIFA and some other sports federations have more member countries than the United Nations.

The upside of this development is that the leaders of sport can claim that they are breaking the colonial scheme of sport, fulfilling the goal of making their specific sport accessible to the whole world, also to the less privileged people and countries. By involving new groups and giving each new member state a vote, they can with some right say that they are making sport more global and more democratic.

But there is also a remarkable downside. The one-country-one-vote system is also yielding a lot of power to countries with no particular engagement in a given sport, and – if you take into account that the generous amounts are granted without any strict control over their use – power is also given to sports leaders who may think more about their own fortune that about the fate of their sport.

When we are talking sport in a development context, this is a factor we have to take seriously. Can we say without blushing that the fortunes that the international federations have spread out over the developing countries for the past 25 years, have had an important impact on sports participation in the populations? Are the international federations efficient and reliable partners in the expansion of grassroot sport?

At the 2nd Magglingen conference for sport and development in Switzerland in 2005 I had the opportunity to briefly encourage small grassroot sports projects to prepare for a situation where corruption in one project could destroy the reputation of sport in development more broadly.

Immediately a middle-aged man grabbed the microphone and declared he was “livid�?: There is no corruption at all in sport for development, he stated, and I owed everybody an apology!

I was quite surprised by this reaction. And I became even more surprised when I found out that the furious man was the Zimbabwean Tommy Ganda Sithole, prominent IOC director of international cooperation and development.

It is not only surprising, it is deeply worrying if a man in that position rejects that sport is vulnerable to corruption everywhere, even in developing countries.

The fact is that sports organisations are too often breeding grounds for corruption, and there is no real interest in stopping this state of affairs from the inside. On the contrary, the power base of the leadership of sport is built on this scheme of clientelism, of quid pro quo.

The family culture

Those few sports leaders who dare speak up against this system of governance, are met with ridicule, exclusion or marginalisation. Such behaviour is not only threatening the power structures, being illoyal to your leaders is also incompatible with the cultural concept that sports leaders like to promote: Sport as a family.

Over and over again, Sepp Blatter and his likes refer to their sport as a family, the football family, the family of volleyball and above all the all-embracing Olympic family.

The family word may produce good feelings in the corridors of power, but is not as innocent and heart-warming as it may seem. The family unity is also used as a shield against open internal debates.

In a family we are loyal to each other. We do not have any real conflicts of interest. We do not hang our dirty laundry out in the open. And at the end of the day, Daddy knows what is best for us.

If sport was regarded as a community rather than a family, conditions for the debate would change radically. They might even become truly democratic. The family is based on the idea that we all share the same interests. Democracy is based on an understanding that we have different interests and it offers us a way to resolve our conflicts. And top do so, it is a prerequisite that the conflicts are visible and can be discussed publicly.

If the affairs of sport really were a matter for sport only, we could leave the family members to take care of themselves. But during the last 30 years, sport has developed into an unparalleled economic, political and cultural power, and it is therefore of fundamental importance to democratic societies that sport takes its internal democracy seriously as exactly that – and stops seeing itself as a family.

Otherwise the world of sport runs the risk of blending into other industrious groups that handle big fortunes, live outside the law, operate freely across borders – and is based on family values. We have a name for this type of organisation – a word borrowed from Italian.

The media as part of the fan crowd

I have now discussed some of the most important internal factors that make sport unable to clean up its governance by itself.

Let me – in equally rough terms – look at those external forces that you would expect to exercise some control.

One is the world I come from as a journalist: The media. I am embarrassed to say that you should not expect too much. Very few, if any, major sport scandals have in the first place been revealed by investigative journalists.

Sports journalism emerged as a twin to sport, in the late 19th century. From the outset, sports journalists has seen themselves as fans, gladly assisting sport with bringing out its message of character building, national pride and peace in the world.

It has probably oiled the media’s willingness to co-operate that sport was always an item that could attract readers and advertisers. And in recent times, the commercial partnership has grown enormously with the TV media as one of the leg in the before mentioned Bermuda Triangle of sport.

So although sport, as I just mentioned, exercises considerable influence in society, journalists are still focused on the battle field rather on the games in the corridors.

To give you an example: When searching in the international newspaper database Lexis-Nexis which covers most of the Western Hemisphere I found only 44 articles mentioning the ISL and FIFA after the decision to settle the case in June. The articles reached only 12 out of the 208 member nations of FIFA.

We often regard the media as the fourth branch of power in democracies. Sport is a notable exception.

Protecting the autonomy of sport

With such a silence from the inside of sports as well as from the media it is hard to blame our elected politicians that they do not react. Why should they?

Sport is regarded as widely popular, and politicians would not like to provoke their voters by opposing sport. Also, sport might single out critical politicians and stop inviting them to getting media exposure at national team games and medal ceremonies.

Moreover, in many countries sport is seen as a part of the independent civil society, a no-go for politicians, and protecting sport’s autonomy is on top of the agenda of all sports organisations.

Whenever the IOC mentions the need for good governance, they also mention autonomy of sport. There is a clear underlying warning to politicians: If they do not listen, sport will react.

Every now and then FIFA issues a bulletin against a member nation’s government for interfering in football’s own issues. Sometimes FIFA might be in its right to do so, but we have seen many cases in which FIFA intervened against governments that tried to stop corrupt football leaders. Ask in Poland, ask in Greece, Kenya, ask right now in Nigeria.

And independently of the reasons, when FIFA threatens a country with being suspended from international football, most governments pull back.

Last but not least, sports organisations prevent political and police intervention by placing their headquarters in countries that have very favourable working conditions.

Home country number one is of course Switzerland where the organisations enjoy special tax privileges plus the same legal status as any local bowling or household association. This means that the kind of corruption that distorts business competition, like in the ISL case, may well be illegal now. But it is still not illegal to hand over personal commissions in relation to internal events, like elections or choosing hosts of sporting events.

So what can we do to demand transparency, democracy and fair play from such important and potent players in a global, billion-dollar entertainment industry, that are intimately linked to the largest consumer good producers, protected by media conglomerates, and blessed with enormous political, financial and cultural influence?

A solution derived from an emerging threat

The solution may be helped forward from an unexpected side, from people that care even less about sport’s integrity and are even more powerful and unscrupulous.

In the past years, the combination of match fixing and illegal gambling on the Internet has become a growing industry and a growing threat to sport – especially to sport as a business.

Match fixing is indeed an impressive threat. Experts assess that the annual revenues in the world gambling market reach 350 billion dollars – out of which 100 billion dollars are derived from the illegal market, dominated by organised crime in Asia.

If the public in general looses confidence in how sports results are made – in equal competition with uncertainty of the outcome – it will not only affect the state gambling companies that finance sports organisations in most of Europe and many other countries around the world.

It will also affect the lucrative Bermuda Triangle seriously and the core business interest of sport, the media and sponsors.

This threat is by nature global, crossing sports as well as geographical boundaries. An increasing number of sports officials understand that a global all-comprehensive threat must be faced with a global all-comprehensive answer.

A global coalition for good governance

Play the Game suggested in 2006 at a seminar organised by the European Council and UEFA, that we let ourselves be inspired by the World Anti Doping Agency which has proved that a legally binding cooperation between governments, supranational institutions and sport can create considerable progress.

We believe it is time to create a new world institution – a “Global Coalition for Good Governance in Sport�?.

This new anti-corruption body should be run jointly by the International Olympic Committee and the international sport federations, by the United Nations, by governmental organisations like the EU and the European Council, and – as a supplement to the structure we know from WADA – should also invite representatives of the media, the scientific community, the fan trusts and the sports business side to the board.

The “Global Coalition for Good Governance in Sport�? should

- define minimum standards for transparency, accountability and democratic procedures

- have administrative capacity to ensure that the minimum standards are respected

- Build up a global co-operation between the betting industry and governments to counter illegal gambling and match fixing

- actively welcome sports leaders and administrators, media professionals, sports researchers and other stakeholders to report irregularities

- have a legal mandate and professional expertise to investigate cases of mismanagement and corruption, including the right to search sports offices, archives etc. without prior notice

- be equipped with right to issue bans against individuals or groups who violate the global standards and suspend those who are under investigation

- be provided with a legal status that enables it to report supposed violations to national or international legal authorities for further trial

- communicate its findings to the public through annual reports, conferences etc.

Though the focus these years is mostly on match fixing, it would be a great failure to focus narrowly on this aspect of corruption which is managed by organised crime.

Also sports organisations and their leaders must accept that they should be held accountable for their practices.

Rays of hope

Last week, the Secretary General of WADA, David Howman, suggested exactly such a WADA-style anti-corruption body to the sports ministers from the Commonwealth countries. He said he will repeat this proposal to the sports ministers from the European Union at their meeting next week.

And a month ago, sports ministers from the European Council agreed to act against match fixing.

Though I may have painted a quite dark picture of sports politics, I see some hope in these recent developments.

More than that, there is a hope in the fact that sport really can be used to more noble ends than filling the pocket and building prestige of a privileged few magicians in sport.

Let us not turn our eyes away from these magicians, let us instead take a much closer look at them and see if their tricks will survive our awareness.

At our next Play the Game conference from 3-6 October 2011 at the German Sport University Cologne, we will once again invite leading whistleblowers, academics, investigative journalists and sports officials to discuss how we can build alliances against corruption and for democracy, transparency and freedom of expression in sport. I sincerely hope that you will take part and contribute with your ideas and efforts to ensure that the many magicians will not make the values of sport disappear.

Let me end on a quote by an author who has highlighted magic more than anybody else, the inventor of Harry Potter, J.K. Rowlings who has said:

“We do not need magic to change the world. We carry all the power we need inside ourselves already: we have the power to imagine better.�?

deutsche variante des datenjournalismus: einer (hier JW) stellt die daten zur verfügung), andere (spOn, taz…) machen daraus texte, selbstverständlich ohne quellenangabe. bspw. taz.de: Markus Völker: In den Klauen der Funktionäre. Die aktuellen Bestechungsfälle von mehreren Fifa-Exekutivmitgliedern zeigen auf, dass der Fußballweltverband ein strukturelles Problem hat

Pingback: Die Autoritäten der FIFA und ihre Ethik-Narren : jens weinreich

Pingback: New revelations: FIFA Excecutives named as ISL bribe-takers : jens weinreich

Pingback: “Bribes as salaries for sports leaders�? : jens weinreich

Pingback: AFR: Hustlin’ for the World Cup – q88ydbgx